Graphic by Yujin Kim/The Choate News

One day, Stephen Lara was driving down the road of Reno, Nevada when he was pulled over by a police officer who asked to search his car. Lara, preferring to keep his money in cash instead of holding it in a bank, had his life savings — almost $100,000 — stashed in his trunk. Upon finding this cash, the officer called the FBI in, seized the cash, and brought it back to the police station, never charging Lara with a crime. The Institute for Justice recently brought to light this story of injustice and many more along with it. Luckily for Lara, he was able to get his money back, but most cases don’t have such a favorable outcome.

Laws such as the one imposed on Lara were first created with the intention of confiscating assets from criminal organizations to prevent them from using those assets for nefarious activities. However, criminal forfeiture laws already exist. Once the court systems prove that money is involved in criminal operations, they have the right to seize the assets. Civil asset forfeiture laws are different because government officials are instructed to take first and ask questions later.

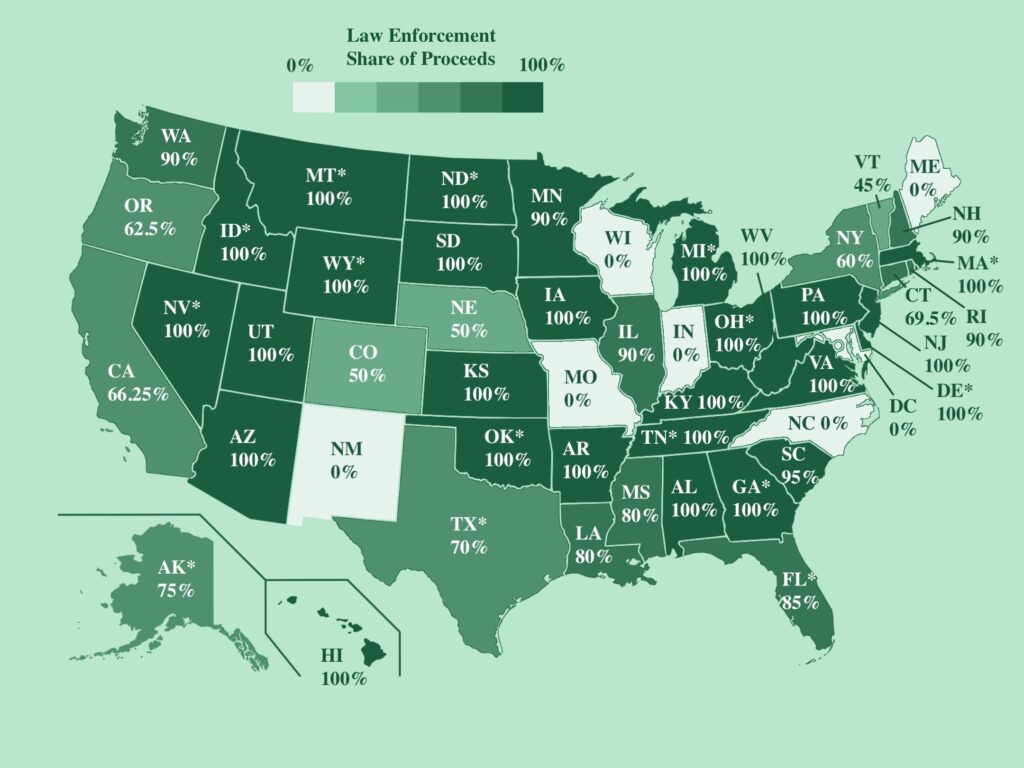

The problem is that police are able to confiscate assets without probable cause. In the case of Lara, the police officer knew that he did not have cause to arrest him but still confiscated his money under the assumption that it was for or from an illegal transaction. What’s worse is that police stations have a financial incentive to engage in these unsavory practices. In the majority of states, when a police station confiscates liquid assets, they — along with the prosecutors — get to keep anywhere from half to the entire sum for themselves. This effectively encourages police to do their jobs poorly for the sake of their precincts’ financial success. In many cases, people whose assets are confiscated are never charged with a crime and cannot afford the legal fees to fight the federal government over the confiscated items.

The need to make change has been brought to light by people on both sides of the table, but few states have made a substantial change. According to the Institute for Justice, while 35 states have passed reforms, only seven have received a grade of “B” or higher on the Institute’s rating scale for how well states protect their property owners. There are two effective proposed solutions.

One — which a few states have already put into place — is a reform of the confiscation policy itself. The ideal reforms would make it easier for the victims of a civil forfeiture to appeal their cases and remove the burden of proof from the citizen in these cases. It would also prevent the local and state police from using the money for operations before any sort of criminal charges or a conviction was levied.

The other solution to the issue of civil forfeiture is a complete abolition of the policy. The clear way to stop the police from abusing the system, as well as the loopholes to it, is to remove the policy as a whole. While it may result in marginally less money in criminal organizations, it’ll prevent a substantial number of innocent Americans from losing their life savings.