“I’ll do it later.” On several occasions, many of my friends skip both breakfast and lunch in order to cram more work in. Kids stay up until 4 a.m. multiple times a week because they’re putting off work until the last possible second. Students here at Choate are under massive amounts of stress and oftentimes can’t cope, resulting to procrastination. The normalization of procrastination at Choate is incredibly dangerous, and we are not properly addressing this problem.

According to Charlotte Lieberman of The New York Times, serial procrastination is caused by unresolved emotional conflict. To cope with mental anguish, we gravitate towards what will bring us immediate gratification, deliberately inflicting harm onto our future selves — and that’s the definition of self-harm, according to Dr. Piers Steel a professor at the University of Calgary. This mental anguish may be caused by intense self-doubt, worry, or emotional trauma. Procrastination is an unhealthy coping mechanism, not some character flaw. It makes sense, then, why people seem to contradict their goals and procrastinate during times of extreme stress.

People procrastinate in different ways. There is what people call “healthy procrastination,” meaning completing low-level homework or chores until they’re motivated to work on a long-term project. These people neglect figuring out what really troubles them. Others procrastinate in more “unhealthy” ways by playing video games, scrolling through social media, or watching Netflix; they admit that they’re self-sabotaging. There are also those who procrastinate but don’t realize it. They spend an hour “working,” but mentally zoned out.

Procrastination can also result from someone having legitimately no interest in their own work. In that case, it’s beneficial for them to assess what they’re doing and why they’re doing it. This seems obvious, but you’d be surprised by the number of things people do everyday — classes, activities, outings — that are unnecessary. Not every moment of every day must be meaningful, but we should try to instill some meaning into it. It’s cliché, but we should foster a genuine appreciation for the opportunities we have been afforded. Otherwise, we run the risk of setting ourselves up for a life devoid of meaning.

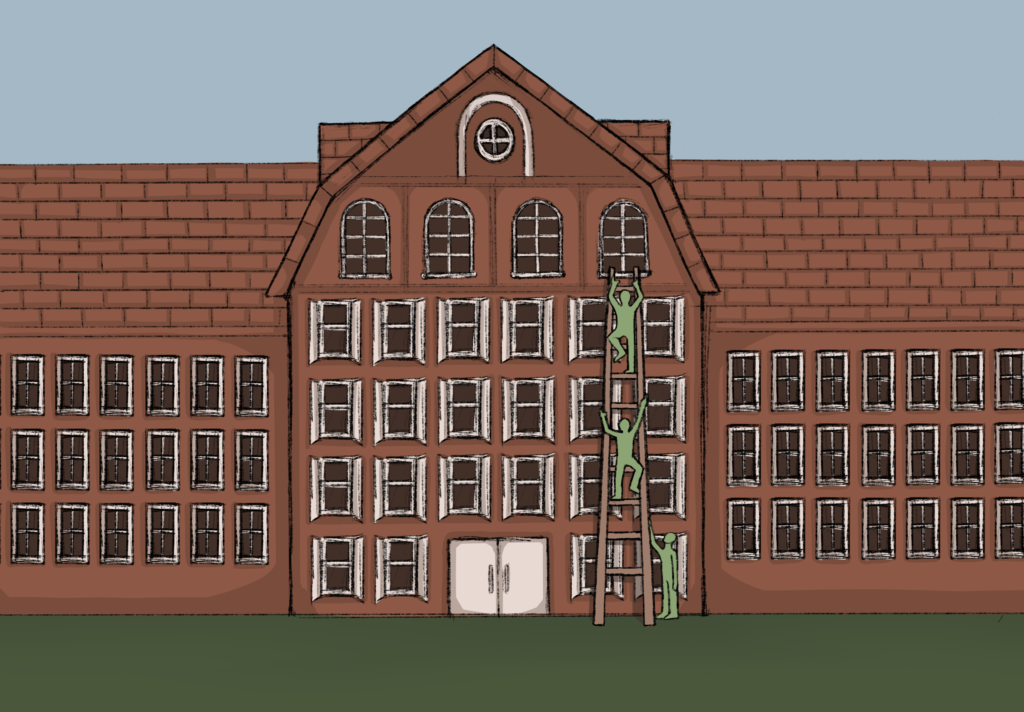

As Choate students, we are particularly susceptible to procrastination for two reasons: we spend much of our time away from home, and we are under a lot of stress. For many of us, the only people really keeping us in check are our teachers and deans. The effect of this cannot be understated. Our brains are particularly malleable at this age, and, for boarders away from home, the development of our self-care habits is left up to us. We stay up and procrastinate because it isn’t so difficult to pull off here, but it can produce negative consequences in the future. Choate is an extremely stressful environment, so in the absence of healthy coping mechanisms, it makes sense why we can fall prey to procrastination.

People don’t seem to recognize the need to address the dangers of procrastination. That’s probably because — to a certain extent — everybody does it. Even if we’re meticulous about our assignments, there’s a solid chance that we’re procrastinating on managing our personal wellness. I wouldn’t categorize a Netflix break during studying as procrastination if I know that I can bounce back. Rather, procrastination is the undeniably harmful, active neglect of our wellbeing. It piles up on all of us. I can’t think of a single person who isn’t neglecting an important conversation that they have to have with themselves.

Although we acknowledge procrastination and even make jokes about it, we’re not actually having the conversations that need to happen. Instead of focusing on the actual causes of procrastination, we tend to focus on time management strategies. By allowing our friends to procrastinate on their health and psychological safety, we are normalizing an especially dangerous form of covert self-harm. Academic and personal excellence should not come at the cost of our wellbeing — a fact that is forgotten by most people on this campus, myself included. It’s not enough to point out this contradiction here.

Too often, we are told that the key to overcoming procrastination is a better, more detailed calendar, but it is crucial to first address the root emotional cause behind procrastination. The New York Times recommends practicing self-compassion, which not only decreases emotional distress but also actively boosts self-esteem and fosters positive emotions like curiosity and optimism. Although this is easier said than done, actively working to make this change will alleviate the danger of procrastination for Choate students.