In one of your classes, you have probably encountered the contrarian: a student enamored with skepticism who disagrees with everything — ostensibly for the sake of disagreement. Contrarianism, although formally defined as the rejection of popular opinion, is usually attached to this negative connotation. Knowing this, should contrarianism have a place in a Choate classroom?

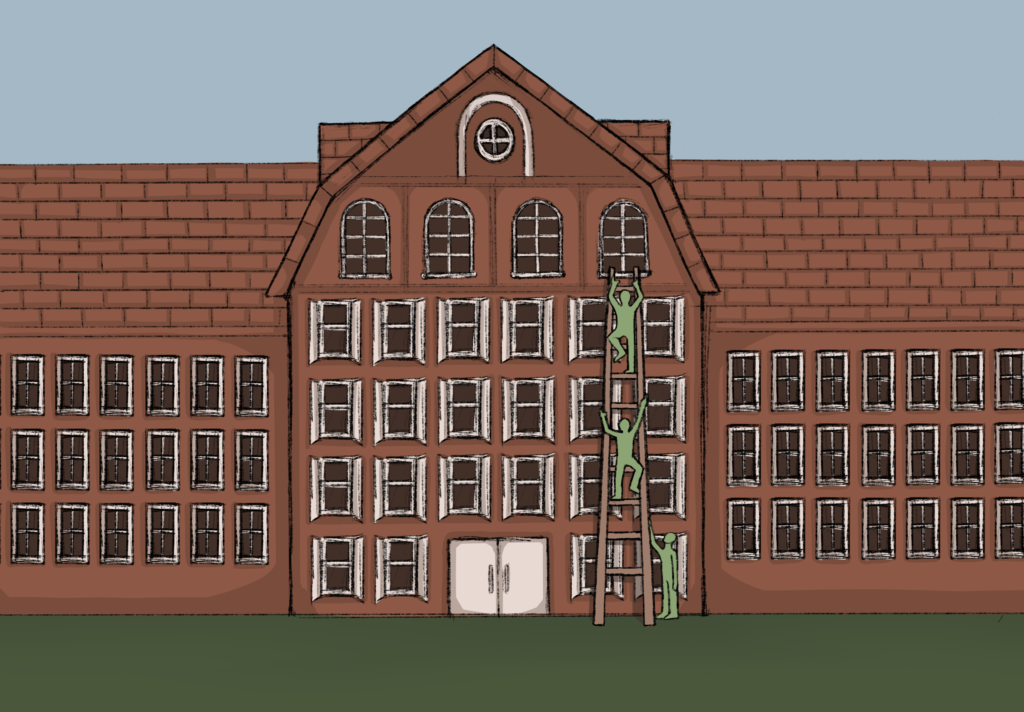

It’s never a good thing to blindly accept the status quo. This idea is the basis of the Socratic method — question everything. In ancient Greece, Socrates believed that wisdom was only attained through the process of questioning. This has played out many times throughout the history of science: a challenge, a discovery, a question, a new discovery, so on and so forth. It would be foolish, then, to accept the popular opinion without attempting to criticize it.

Still, it’d be a reach to say that this is what we do in our classrooms. At Choate, I’ve been asked to challenge, criticize, and question content, sometimes going directly against public opinion. However, by no means does that make me a contrarian — seeking out conflict for conflict’s sake. Instead, I’ve grown to try to look at things with objectivity. In my experience, contrarianism isn’t necessary to create an educated, dispassionate opinion. But contrarianism still shouldn’t be stifled.

Within classroom discussions, our objective isn’t to reach a consensus. Instead, I view them as exercises of our own rhetoric and a check for our comprehension. We share our opinions, listen to those of our peers, and re-evaluate our stances. A discussion is an opportunity to improve yourself, not to disprove others. Dissenting opinions, no matter how questionably argued, are, and should be, welcome in the classroom. In Jonathan Haidt’s talk last term, he made a very valid point about engaging with disagreement: no matter our relationship to the status quo, we can all examine our own opinions.

Disagreement purely for the sake of disagreement isn’t as bad as you might think. While it certainly seems frivolous, it is difficult to challenge our own assumptions and arguments. Maybe that’s why it might feel more exciting to play devil’s advocate. However, with lazy analysis, disagreeing can also be a waste of time. Disagree for the sake of disagreement, but ensure that you can substantiate your argument.

If you want to be a contrarian, you should first learn how to disagree. I’ve found that contrarians tend to inject their own ego into a discussion — they frequently believe that disagreement is the more intelligent or sophisticated method of analysis. This mindset can lead them to monopolize discussion and appear rude, callous, or, at best, socially awkward. These alienating behaviors are what poison the reputation of the contrarian. If a contrarian can respect their classmates, the discussion will become more fruitful.

You will likely encounter contrarians for the rest of your life. Contrarianism is, in a sense, a personality type. The sooner you decide to make peace with a serial disagreer, the easier it will become to understand them. Later in life, you may need to be able to dismantle such defenses — they seem present in almost every dimension of adult life, from the disgruntled client or colleague to the politician on TV. So hear them out — your rhetoric stands to benefit.