Conclusions — they’re not just the end of an era but also the start of a new one. They are transitions from a stage of one’s life to the next, forcing people to morph and adapt to a new, perhaps daunting environment. For me, such an adjustment occurred when I graduated from a same-sex Catholic school in Manhattan to Choate Rosemary Hall. As one might imagine, those of the Convent of the Sacred Heart are homogeneous in almost all respects. For the most part, students share the same ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic background, and gender. My transition to Choate was a complete culture shock.

One thing I noticed immediately about Choate was that there are boys everywhere. They sneak up on you in the dining hall; they fill the pathways with oversized, not-yet-controlled teenage bodies; they monopolize the gym; and they charge classes with an air of pubescent testosterone. In middle school, something so much as a shoulder bump would’ve convinced me that I was in love. It was at Choate that I finally learned that cross-gender friendships were not only real but normal — a valuable lesson that many of my peers at Sacred Heart have yet to learn.

The flexibility of the dress code was another bombshell. At the Convent, we were required to wear uniforms all the time. Clear nail polish was frowned upon and makeup was utterly forbidden. Teachers would use tape measures to ensure that skirts were no more than two inches above the knees. If a girl were to violate this rule, she was subjected to the “Skirt of Shame,” a ghastly uniform stretching lower than any girls’ ankle. So, naturally, I was shocked by all the freedom I had been given at Choate. That there was no commandment for any girl to wear a skirt was a revelation — suddenly, I could wear virtually anything I wanted. Slowly, I veered away from the steadfast philosophy that showing skin was immoral. I discovered that dressing for the day could be more than a routine; it became a way to express myself.

Perhaps the hardest change to accommodate was the sudden need to defend my religion. In my youth, I had only been surrounded by other Christian girls, people who shared and understood my faith. Following the transition to Choate, however, I quickly learned that many outside the Convent held misconceptions about Christianity. It was up to me to debunk these fallacies. For instance, people assumed incorrectly that I was homophobic and pro-life. In fact, while it is true that lesbians at the Convent were shunned and abstinence was heavily promoted in health class, I, personally, hadn’t even begun to grapple with such politically-charged issues. It was only after coming to Choate that I slowly adopted my opinions on these issues and learned to defend them against critics. Gradually, I took the Christian morals that I was taught as a child and shaped them in accordance to the lessons that I have learned elsewhere — eventually forming my own worldview.

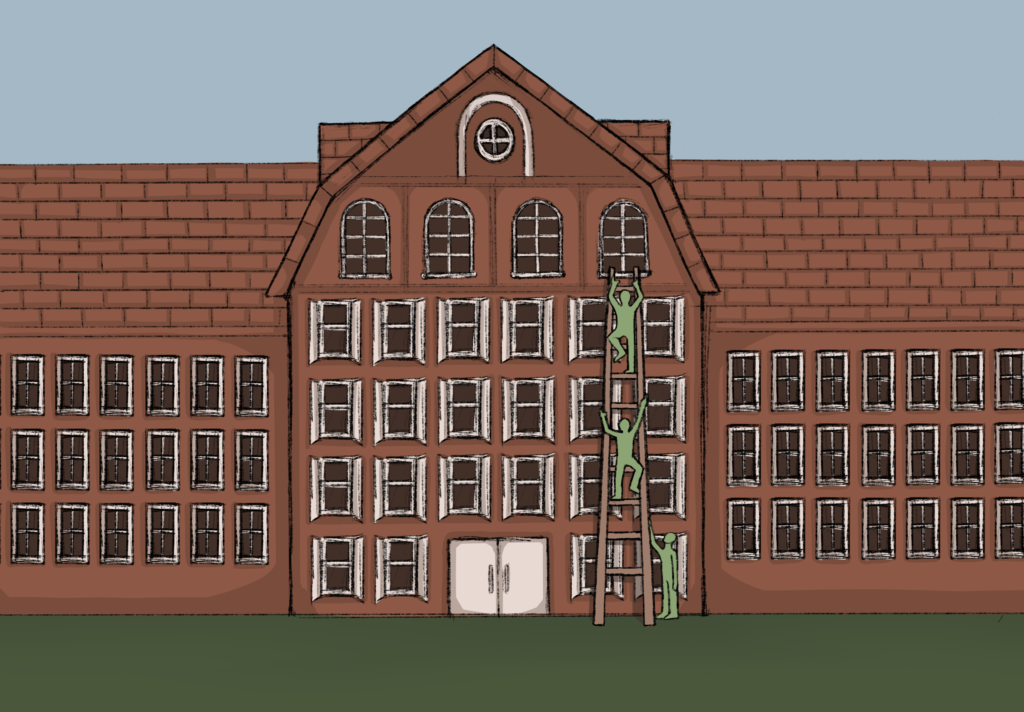

Though Choate has taught me to open my mind, it remains a bubble. Granted, it is a much more diverse bubble than the Convent, but it is a sheltered one nevertheless. Seniors will soon matriculate into a new bubble: college. But the conclusion of their high-school experience doesn’t mean that they’ve learned everything there is to know or that their ideologies must be set in stone. So, a word of advice: embrace the changes life throws at you. As you enter new environments, you’ll come to realize that nothing is really concluding — it’s just starting anew.