On April 8, I and five fellow Choate students woke up bright and early on a Sunday morning and boarded a bus to Deerfield to participate in the Asian American Footsteps Conference. We went to connect ourselves a little more with the Asian-American experience.

The day started on a high note: a K-Pop dance performance and an interview with Wong Fu Production’s Wesley Chan and Philip Wang, who talked about being children of immigrants, coping with both Asian and American expectations, and blending in with many cultures at once. Most interestingly, they spoke about their experiences “painting themselves red” — emphasizing their Asian-ness instead of trying to blend in with American culture.

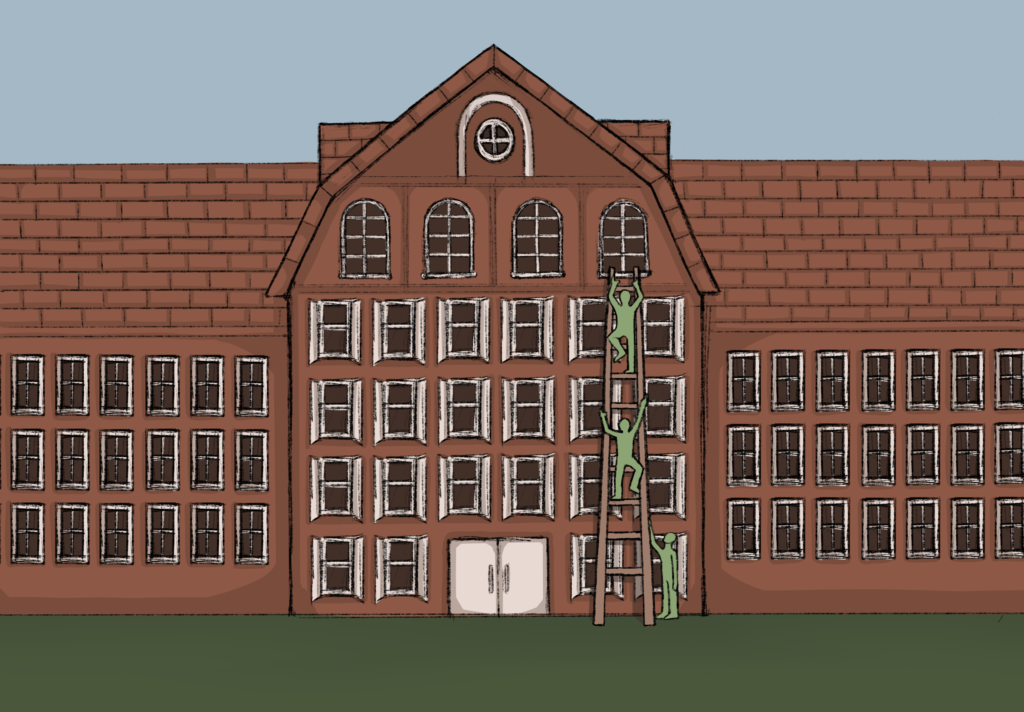

Then I met Asian students from other boarding schools. We danced to K-Pop, talked about college admissions through an Asian perspective, and addressed the challenge of breaking down the idea of the “model minority” — that Asians are the “acceptable” minority, that they are the ones who end up as doctors and lawyers, that they are the ones who care only about good grades, that they don’t cause trouble. The perspectives and ideas that I gained at the conference have lingered in my head. A few weeks on, and I am still pondering and contextualizing them.

I think that the best conversations happen over food. So I wasn’t surprised when, a few days after the conference, the topic of Asian representation came up over dinner. The conversation had shifted to people of color, and a friend had listed black and Latinx people under the category. I interjected, saying, “And Asians, right?”

Even if Asians aren’t often at the center of the people-of-color discussion, it doesn’t mean they aren’t, in fact, people of color. America, of course, is made up of many racial minorities. Asians, along with those of other minority groups, are frequently forgotten. People, even here at Choate, often turn a blind eye to harmful prejudice against Asian people.

The Choate community is incredibly diverse and very accepting. Yet, Asians are reduced to a “model minority,” microaggressions such as “You’re Asian; come help me with my math homework” and “Of course you play piano — you’re Asian” occur. Sure, those microaggressions may be seen as “good things” — after all, it is a mark of accomplishment to be good at math or proficient in an instrument.

Microaggressions are not compliments; on the contrary, they are damaging. These assumptions discredit the hard work that goes into being academically proficient or musically skilled. No Asian is good at something because she is Asian; she is good at something because she worked for it.

Moreover, for every Asian who does well at a stereotypically “Asian subject,” there is another that doesn’t. At Deerfield a few weeks ago, Philip Wang admitted to feeling frustrated that, as a younger man, he couldn’t completely claim his Asian identity because he wasn’t good at math. The Asian stereotype inadvertently casts Asians whose interests happen to lie outside of math and music as rejects. And it suggests, however indirectly, that one’s worth depends not on an innate humanity but rather on a skill or so-called talent.

I, too, am guilty of attributing my traits to the Asian stereotype. Too often, when faced with a compliment, I brush it off by saying, “Of course, I’m Asian.” At some point, I’m sure I meant that as a point of pride — taking ownership of my identity. However, the way that my statement manifested itself was not empowering but restrictive. It was as if I had only done well because I was Asian, and not because of anything else.

To me, “model minority” sounds like saying, “Well, Asians are ‘better’ than other people of color. But they’re still a minority; they’re still ‘other.’” Asians may be approved, but they’re not accepted.

Luckily, there is more than enough space in this world to work on the problems of multiple people, multiple races, and multiple ethnicities. Now is a more fitting time than ever to address these problems, including those unique to Asians in America.