We recognize several problems with the Choate visitation policy. The first is its heteronormative nature. Last year, Choate renamed its “co-ed” policy “visitation.” The new wording, on page 33 of the Student Handbook, reads, “Visitation rules apply equally to heterosexual students and to those who identify as gay, lesbian or bisexual.” But what, really, has changed for individuals that do not abide by the heterosexual paradigm?

Since (of course) the school does not identify and categorize the sexuality of its student body, defining who needs permission to be granted visitation with whom remains a challenge. In fact, the Handbook’s new language fails to create an equal set of rules for all students in romantic and/or sexual relationships.

One solution might be found in Andover’s system, which does not distinguish among genders. Choate could emulate Andover’s policy of visitation—essentially, any visitor, at any of the allowable times, needs permission before entering another’s room—while adjusting it to Choate’s schedule.

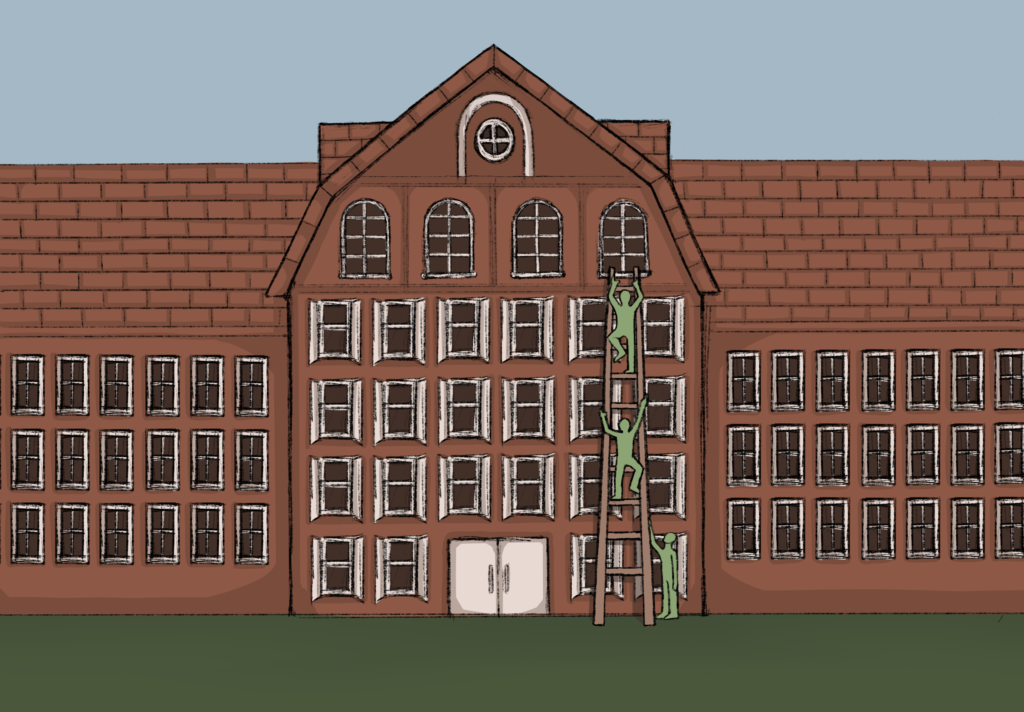

Moreover, by not giving its students ready access to private spaces, Choate often forces its students to break campus rules, such as closing the door to a dorm room or entering a restricted area, in order to spend time—even if simply to have a personal conversation—with a member of the community of a different gender. This is problematic, as these actions result in students associating the cultivation of healthy relationships with the breaking of a school rule.

Another problem is the inconsistency of visitation guidelines between dorms, and how each faculty member enforces them. In some dorms, the strictness of the policy waxes and wanes depending on the adviser on duty. One adviser might grant students visitation and set them free to close and lock the door. Another might frequently check in on students and force the door to be fully open.

Although many issues exist because of visitation, there are also many valuable aspects to the current system. Choate has taken an active role in making students aware of the presence of sexual misconduct on high-school campuses (remember the provocative plays Slut and Now That We’re Men performed in the PMAC last fall). Many students and faculty agree that visitation is important for the purpose of creating a structure that discourages sexual misconduct and ideally prevents these cases on campus. Choate may feel hesitant to relax its visitation policy in fear of jeopardizing students’ safety.

We have discussed this issue with several faculty members, and it seems as though the main issue regarding the reformation of the visitation is not the policy itself, but, rather, the issue of consent. Education on consent lies in the hands of student groups as well as the administration. Going forward, we, along with other student groups, will try to work with the administration to create a newer, more progressive system of visitation.