As I sat on a MetroNorth train at the end of last long weekend, I tried to reflect on my exciting days in New York City, mulling over how I could use my four-day-long catharsis as motivation for the last weeks of winter’s drudgery back on campus. I thought about how my weekend days lacked the rigor of student life and how that ought to push me toward dedicated studying, about how the hyperactivity of New York disoriented me slightly and caused me to long for the simplicity of Choate days.

Most of all, however, I thought about my wallet’s dire straits after a weekend of living beyond my modest means. My wallet’s worn and ripped interior housed a miniscule amount of cash. I knew that after attending the First Hurrah, one of the many social expenses at which I obsequiously throw my funds, I would remain with minimal funds to last me the remainder of the term. Through careful social isolation and prudence, I might have been able to stretch these limits, but the call to contribute to the senior class gift caught me off guard.

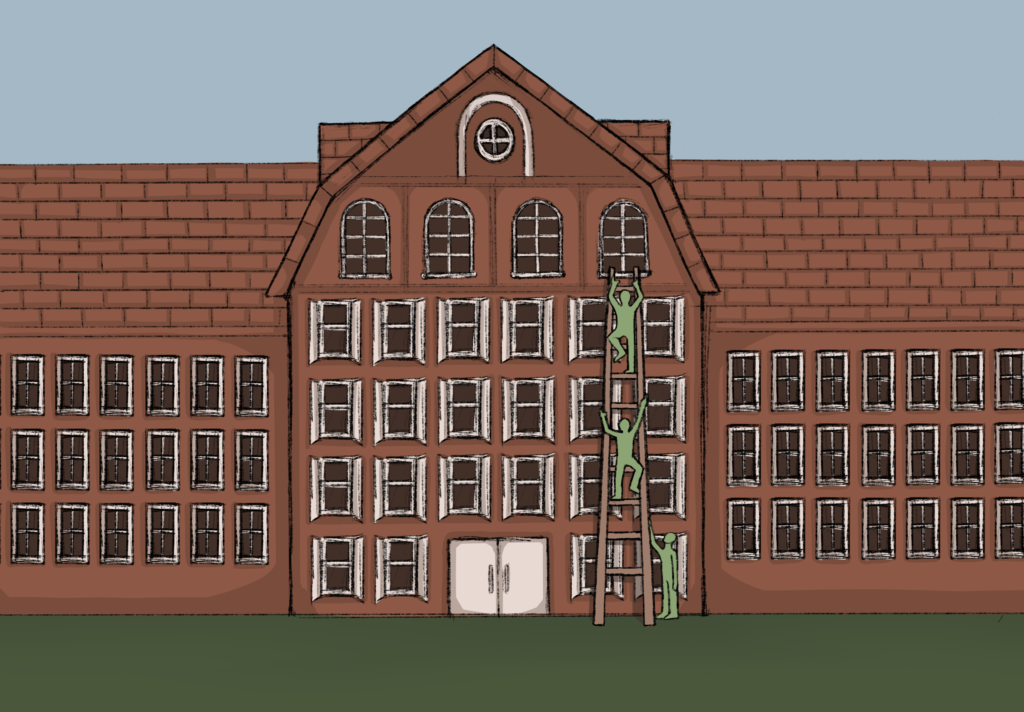

Had I been left alone to consider whether or not to contribute to the senior gift, I would still have joined my classmates in donation. I relish Choate’s strong financial aid program; without it I could have never dreamed of attending this school. However, in the days leading up to and during the senior gift collection process, I had to make my decision in a coercive, anxious environment. The collectors of the senior gift appeared at school meeting, compelling our class not to donate an impressive amount, but to reach full participation. Thinking back on the donation process, I realize that the primacy placed on full participation caused me undue stress and likely limited the total amount collected.

A participation-based collection process produces anxiety for lower and middle-income students, like me, for whom financial decisions require deep consideration. Although the organizers of the drive emphasized that any donation amount is acceptable, I felt as though any significant donation I made would seem marginal and implicitly insufficient. I heard my peers urge each other by saying “just give a few dollars,” as though they couldn’t believe that, to me, a few dollars could constitute a generous, consequential donation. This assumption caused me to internalize the notion that, in the eyes of my peers, what little I could contribute was essentially a copout, a contribution meant only to bolster a percentage. Therefore, I became frantic, assessing how best I could scrounge up a “significant” donation, one that would display my gratitude for the financial aid program while adhering to internalized messages regarding a substantial gift. This internal tumult only grew as I watched my classmates walk to the donation site and ring the loud bell that signaled each new donation and urged me to give.

Beyond its personal toll, the participation-based collection process may also be limiting the drive’s ability to gather enough money for its cause. From appearances, this possibility doesn’t concern the organizers of the event: the organizers focus on achieving a 100 percent participation rate, regardless of gift size. To their credit, the drive’s management has, throughout my time here, boasted near full participation, while the senior classes at elite institutions with generous alumni, like Dartmouth College, only range between 60 to 75 percent participation over time. Choate’s success in this arena may indicate that our students appreciate and take ownership of the School; the high participation rate certainly pairs well with the mushy “I Love Choate” video recorded during the drive. However, high participation may not translate into high donation yields. When the organizers place a premium on giving for the sake of participation, those with the wherewithal to contribute significant amounts may feel compelled to give, only in order to help achieve the elusive 100 percent. If the organizers were to root their campaign in a goal amount, or even a simple increase in donations from the previous year, students with greater ability may be incentivized to give greater amounts. This method of encouragement would also combat the pressures on lower- and middle-income students.

At one dining hall table, while discussing my feelings on the senior gift with my peers, a friend suggested that a focus on full participation may unify our class, engendering the excitement of collective action among our form. However, when I reflected on my donation, I hoped that my contribution would pragmatically enable more students to share my experiences, not simply achieve some idealistic, symbolic end. Although it could never equal the amount that Choate has invested in me, I wished that my donation, in conjunction with the donations of my class, could offer a student like me the chance to go abroad for a debate tournament or to afford an expensive textbook. Given this vision, I hope that the senior gift team will take steps to minimize the gift’s impact on lower and middle-income seniors, while maximizing its value to those we leave behind by changing its approach to one that is amount-based rather than participation-based.