We often bill Choate as a progressive, left-leaning campus, and many members of our community identify that way as well. We talk extensively about diversity, equality, and justice. We make efforts to publicly show how inclusive we are as a school. But I can’t help notice the many ways in which we fail to practice what we preach.

As much as we want to deny it, marginalization exists at Choate. It can sometimes be institutional, but most of time, it manifests itself in subtleties of action and conduct. And the most significant way in which I’ve witnessed marginalization happen here — both to my peers and to myself — is through our recognition of leaders on our campus.

Leadership is gendered at Choate, and I know that doesn’t sound immediately believable. Several of our largest student clubs and organizations are led by female students. Female leaders exist and are prominent within the C-Proctors, the JC, Peer Educators, Assessment Team, the Prefect program, and more. Even the President and Vice-President of the Student Body are women.

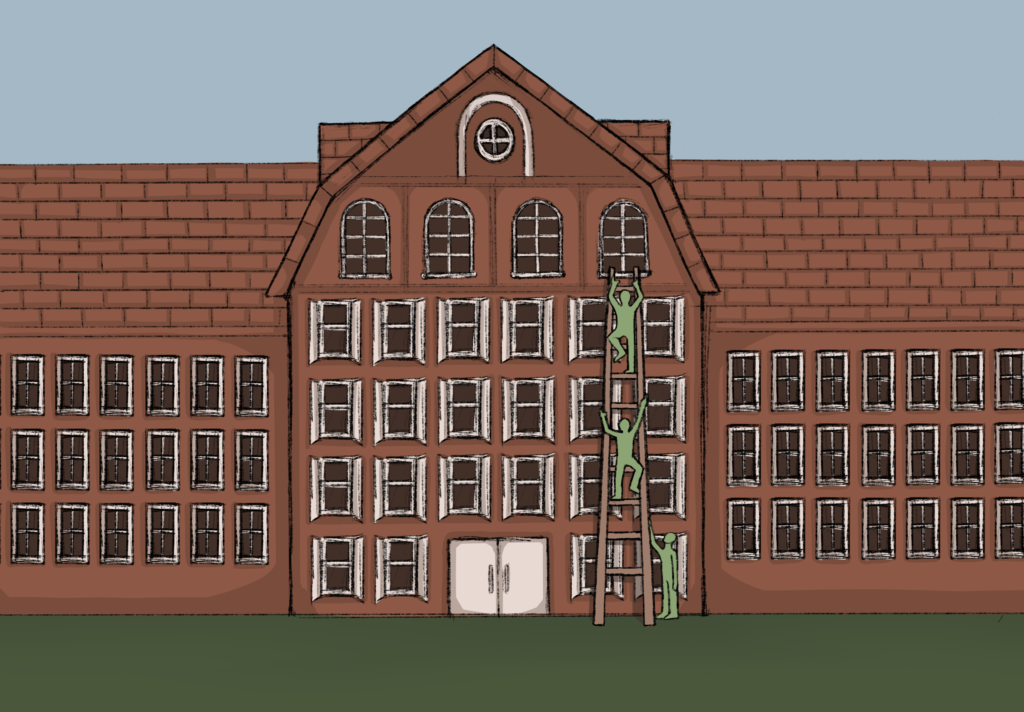

However, I’m asking us to consider the ways in which leaders are recognized on campus. In my experience, the leaders that are elevated, embraced, and celebrated by the community at large tend to be male students, and more often than not, these male students are of a particular brand: they are the self-avowed feminists, the “woke” activists, the leaders who preach about making substantial, progressive changes to our institution.

I’m not arguing that we shouldn’t recognize these men. The work that they do is often important and impactful, and I don’t think we should discourage the type of leadership that they exhibit. But I’ve also watched as many of my female peers, who are also feminists, “woke” activists, and want substantial, progressive changes, are overlooked again and again even though I know they put in as much work as their far-more-often-recognized male peers. A cabinet of a cultural or social justice club on campus could be gender-balanced, but the male leaders are often the ones being publicly acknowledged, invited to meet special program speakers, or asked to talk to important visitors.

There are instances in which female students have been spoken over or outright ignored, either by fellow students or adults in the community. In fact, just two weeks ago, a male student and I were speaking to a dean and although I was doing most of the talking, the dean would only look at the male student when responding, as if I wasn’t a part of the conversation.

It’s almost as if we celebrate male activists because we expect them to not be so progressive, while we ignore female activists because we expect them to be advocates for whatever causes liberal society has deemed important. I’m not saying that recognition of women doesn’t exist at all. The past two winners or co-winners of the Princeton Prize in Race Relations from Choate have been female leaders on campus. But I’ve also seen how some faculty members or deans continually prefer or recognize the leadership of female students who tend to be more measured in their activism, if active at all.

If female students are passionate about activism, we are often seen as “too emotional” or “too aggressive.” I know this is the case because I’ve been described as both. I’ve been told that my passion for the work that I do or want to do inhibits my ability to negotiate and collaborate. Yet when my male peers get just as assertive about issues that they care about, they are rarely told that their behavior doesn’t make for good leadership. When I worked on the dress code petition, I was dismissed by certain adults in ways that my male peers who worked on the dress code petition weren’t. They were still publically recognized by those adults later, despite disagreements on how we all handled the issue.

My time at Choate is almost over. There is little that I can do now to change my experience here — an experience, I might add, that I have truly loved and cherished. But I’ve also been frustrated, and I’ve spent substantial time denying my own experience and experiences of others. It’s time that I finally trust what I have seen, heard, and felt, and I’m asking you to do the same. Thinking that these problems do not exist is exactly why they persist, and there are still many members of our community who refuse to reflect on their actions and their effects, however small.

I have spent months trying not to write this article because despite my bravado, I fear the backlash that I will inevitably get. However, I am writing this now: not for me, but for the women who will succeed me. The young women on this campus who are loud, proud, unapologetic, strong, and driven. The same young women who deserve to be recognized by the administrators and teachers who can help them make a difference on this campus.

So I’m asking that you don’t overlook them because you immediately gravitate towards their male peers. Ask yourself why you make the assumptions that you do, then change the way you think about leaders on this campus. That is what inclusion truly looks like. This school is not free of the -isms we seek to overcome. Amending the lenses through which we select the people to lead this campus, implicitly or explicitly, is one way to overcome some of the issues that our students face.