If I had to summarize the theme of the Judicial Committee speeches in one word, it would be “administration.” If I could use two, I would add “horrible administration.” And if I were given a full sentence, I’d say, “The administration is hiding insidious problems within its justice system, and we need a candidate who can reform the decaying system from the inside out!”

The consensus among these speeches is that Choate desperately needs change, and we need to choose the students most suited to making change. It’s a pretty good campaign riff, no doubt.

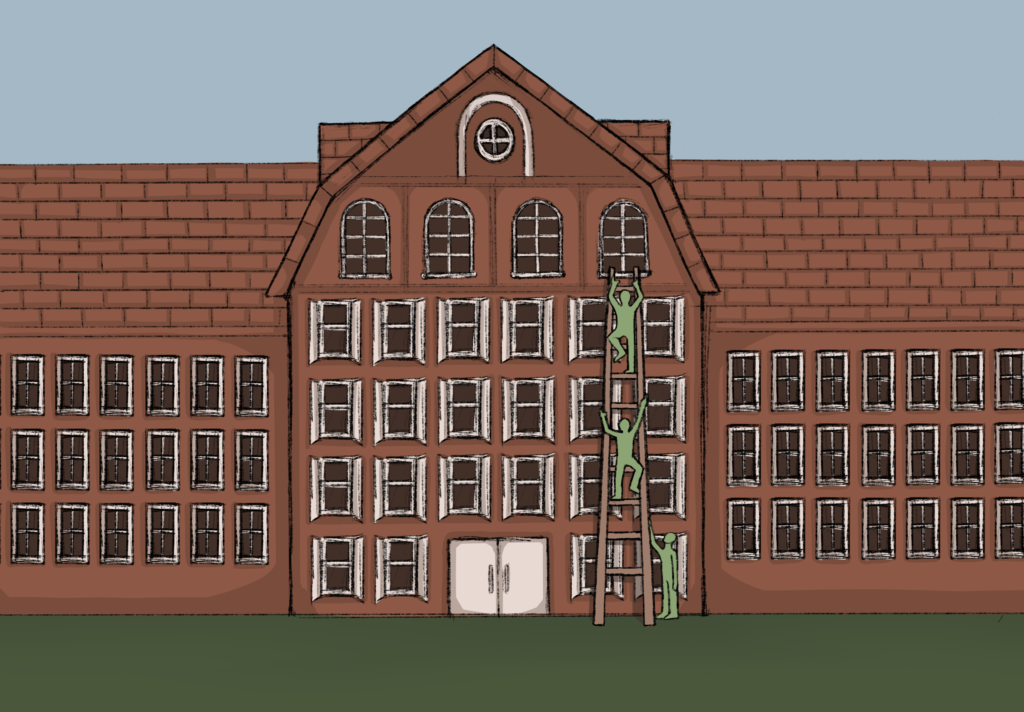

If the purpose of electing student representatives is to bring radical change to the administration, it raises the question: what, honestly, has any elected official done to change the way Choate works? Despite the yearly promises for administrative upheaval, Choate remains nearly institutionally identical to its old system .

This is because voting someone into office simply because they promise to spark a revolution contradicts the fundamental purpose of student representation: to assist, not destroy, the administration. The cooperation between students and Choate faculty attests to everything we’re doing right: from clubs to the Judicial Committee, Choate relies on student-driven initiatives. In the past year, we have allowed the entire student body to vote on the future class president, inspired plans to provide free tampons in all buildings, and made it possible for clubs to meet in the Humanities building. All of these changes come from effective student cooperation with the administration.

But the path to election doesn’t reflect that. Ironically, the people most likely to be elected are the ones giving speeches about how they’re going to put an end to the current administration.

This may seem shocking, but for the most part, the administration functions because it has reasonable policies. Choate isn’t a prep-school autocracy. If changes need to be made, our school has procedures in place to recognize and respond to those needs accordingly. But cooperation doesn’t make a compelling JC speech.

In other words, misery sells. Our identities at Choate are rooted in discontent. It shows in the type of student officials we elect, the editorials we publish, the way we talk about Choate in our everyday conversations. If a reason for dissatisfaction isn’t there, we invent one.

Constantly demanding revolution within governing systems is self-defeating: first, because promises to fulfill these demands are often used to garner votes rather than institute actual change, and second, because a revolution usually isn’t necessary. The “necessary change” cited by so many JC hopefuls is ambiguous because no one can define what it actually is. Choate is rebelling against an enemy that doesn’t exist.

Ultimately, there is only one solution to this problem: substantive change. Rather than continuing to depict the administration as an oppressive force, we must put our complaints aside and advocate for progress. If we try to lessen — or, dare I say, stop — our calls for revolution against an imaginary enemy, we might actually pave the way for institutional change.