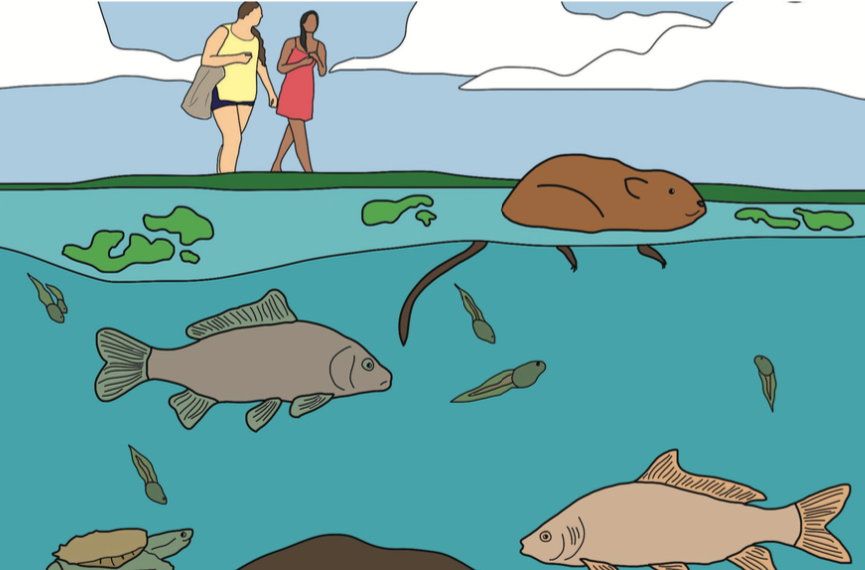

Imagine crossing the bridge from the Lanphier Center to the Science Center. On the right side, you see several turtles sunbathing on a log; on the left, you see a giant koi splashing water in its wake. This is only a sample of the many organisms that live in the Science Center pond — a thriving ecosystem in our own backyard.

There are many fish species in the pond, including koi and American eels. However, the koi fish did not reach Choate naturally. Mr. Joseph Scanio, Director of the KEC, explained, “Kois that live in the pond are not native to Choate. People buy them, and, when they feel that they cannot afford to care for them, they do not kill them but abandon them in the pond.” Kois have been known to live for 50 years, which may explain their longstanding presence on campus.

Also found in the pond, American eels migrate to sea to lay eggs and return to freshwater — journeying as far as 3,700 miles after mating. These animals live up to 25 years and are nocturnal. The American eel faces a very high risk of extinction in the wild due to a lack of habitat availability and a sensitivity to low dissolved oxygen levels.

The turtle species within the pond include snapping turtles and eastern painted turtles. Snapping turtles can be 20 inches long and have a combative nature when out of the water, using their powerful jaws to attack. They can move their head and neck freely, allowing them to actively hunt invertebrates, fish, frogs, reptiles, birds, and small mammals. Eastern painted turtles, on the other hand, are much smaller — only about ten inches long. The eastern painted turtles hibernate in the mud at the bottom of water bodies during the winter.

Along with these organisms, there are salamanders, dragonfly nymphs, flies, beetles, hawks, cardinals, and many other species that take advantage of the pond. Micro-organisms like daphnia (or water fleas) are also present. These miniscule, transparent, aquatic crustaceans mainly feed on algae and bacteria.

These organisms form an expansive network of symbiotic relationships. “You can see many different interactions among various organisms in the pond,” Mr. Scanio commented. “You can see every single interaction you can imagine: competition, predation, parasitism, mutualism, and pollination.”

The pond’s success as a hub for campus life can be attributed to its recent renovation, which has allowed for a variety of life to flourish. During the summer of 2010, the pond, which had not been dredged since the Science Center was built in 1989, was dredged to remove sediment that had accumulated over the years. “After dredging, Facilities decided to design both the vegetation and the contour to be a good environment for many species living in the pond,” Mr. Scanio said. “Different species require different habitats. Amphibians prefer shallow areas, whereas big fish and their predators live in deeper areas.”

There are several factors that can alter the pond ecosystem, including seasons, predation, and human activities. During the winter, as the weather becomes colder and daylight gets shorter, many of the species hibernate or migrate. However, the species that stay in the pond adapt to cold weather. Dr. Heather York, a Biology and Environmental Science teacher, said, “Only the top of the pond freezes, and the ice acts as as an insulator for the water below. This allows the tadpoles, fish, insect larvae, and other aquatic organisms to stay warm during the winter.” The pond’s muskrats, on the other hand, build burrows to prepare for winter, and snapping turtles bury themselves in mud.

Prey-predator relationships affect species as well. Mr. Scanio theorized that the pond’s frog population decreased when fish were introduced to the pond. The fish were likely eating the pond’s tadpoles, causing their numbers to fall. Many bird species, especially the singing birds, visit the pond to escape from the predators, namely red-tail hawks and Cooper’s hawks, which specifically target small birds for predation.

Although small, the pond and its many organisms represent the biodiversity of Choate as an ecosystem. Why is it important to maintain the biodiversity on campus? Sophie Mackin ’18, a Head C-Proctor, said, “An ecosystem has an interconnected system, which allows different species on campus to live. Disruption in one species may disrupt the ecosystem, and it would lead to many devastating effects. The disrupted ecosystem not only disrupts animals, but also us.”

“Having biodiversity is a great indicator of whether the environment is healthy or not because biodiversity implies a healthy environment where many species can live,” Danielle Young ’17, the President of Students Against Climate Change, added. “The environment is a reality that we all have to face. It intersects with many realms of identity and invites many different communities to come together.”