A walk through the woods of the Kohler Environmental Center (KEC) often unearths unnatural specimens. A rusting red truck rests on the streambed covered in bittersweet vines, a dirty sink leans under large oak trees, an old stove crouches among the bright yellow flowers of lesser celandine, and an unwanted roll of carpet blends with the mud beneath large skunk cabbages.

The KEC, home to Choate’s four-year-old Environmental Immersion Program, sits picturesquely among the fields and woods of an undeveloped area of approximately 130 acres, 108 of which Choate purchased in 1935. Before Choate, the property belonged to Mr. Joel H. Paddock, who for decades hayed the fields. The homestead and old red barns on the southwest section of the land still bear the name Paddock Farm.

It is difficult to imagine the woods by the KEC in any fashion other than how they look now. But a little digging in the archives and aerial photographs display the land’s transformation from clear fields and orchards to secondary growth forests. Along the way, touchstones such as the truck, stove, and sink have remained, marking the incremental transition from farming to trash disposal to environmentalism— between past, present, and future. They speak of a narrative similar to much of New England’s after decades of extensive farming in the 1800s.

Mr. Kevin Wall, a fireman for East Haven and a hay farmer who also raises grass-fed cattle, comes from a family of farmers. His grandfather began taking care of Choate’s cattle and haying the Paddock fields in the 1950s, and Mr. Wall continues to hay these fields today. Last spring, he stopped by to talk after what looked like a day in the sun, sporting streamlined sunglasses and dirt-stained blue jeans.

Mr. Wall said, “Dumping used to be kind of an old farming practice. People would get done with cars and stuff, and back then there wasn’t really a scrap market value or anything like that. So they would just park them in a hedgerow somewhere, and then everything eventually would just grow up around them. That was normal back in the thirties and forties and fifties — before all of the environmental concerns and everything else.”

Indeed, the American environmental movement is relatively young, forming on a national level only around fifty years ago. Rachel Carson published her seminal book Silent Spring in 1962, and the first national Earth Day was organized in 1970. Still, why were people dumping various appliances on their land?

“The farmers, they had no place to put this stuff. There was no place to take it,” said Mr. Robert Beaumont, who agreed to help explain some of the history behind Wallingford’s landfill.

A tall man with sharp eyes, Mr. Beaumont, the chair of the Wallingford Utilities Commission, is involved with the In Memoriam Cemetery Association, and is the Vice President of the Wallingford Historical Society after stepping down from presidency. Mr. Beaumont knows much about Wallingford’s history; he has lived in the town for over seven decades, and the Beaumont family has been in Wallingford since 1780. What he doesn’t know himself he quickly gleans from an array of townspeople.

For the most part, Mr. Beaumont dismissed the KEC’s rusting appliances as the old norm, as it was all before a coordinated solid municipal system. He explained what it was like when he was growing up. “Before the house that we lived in had been built, which was sometime back in the 20s, apparently there had been a low-lying area nearby. I remember helping my father dig up the small vegetable garden that we owned. And there was no telling what we’d find.” He surmised, “The area had probably been the neighborhood dump.”

Mr. Ian Morris, a longtime Choate science teacher who retired last year, also had a similar story. After arriving in 1989, he worked to convert the old Paddock Farm homestead, where he was living, into a beautiful yard, orchard, and garden. Mr. Morris filled the dumpsters with urinals, mattr esses, bedspreads, old sheds, pigsties, metal, and concrete reinforcement, while pulling porcelain, gears, and bits of metal out of his garden beds. The barns by his house, which were used to store hay bales and farm equipment during the Paddocks’ time, are still full of old heaters and rolls of black shingle paper, stored by Choate for a use that still has yet to emerge.

Mr. Ian Morris, a longtime Choate science teacher who retired last year, also had a similar story. After arriving in 1989, he worked to convert the old Paddock Farm homestead, where he was living, into a beautiful yard, orchard, and garden. Mr. Morris filled the dumpsters with urinals, mattr esses, bedspreads, old sheds, pigsties, metal, and concrete reinforcement, while pulling porcelain, gears, and bits of metal out of his garden beds. The barns by his house, which were used to store hay bales and farm equipment during the Paddocks’ time, are still full of old heaters and rolls of black shingle paper, stored by Choate for a use that still has yet to emerge.

Choate had a couple of other small landfill sites, according to Mr. Morris: one in a wet valley under a boardwalk behind the Science Center and at least one in the woods off the cross-country course.

However, a relatively new and well-coordinated solid municipal system in Wallingford has helped mitigate appliance dumping. The town dump is located at 25 Pent Road, off South Cherry Street. It is in the utilities and industry section of Wallingford. A water treatment plant, a BYK Additives & Instruments factory, and electrical utilities are all a couple of blocks away.

According to Mr. Beaumont, this area has been a town dump since the twenties. It began as an open landfill that would occasionally catch on fire and require the attention of the town fire department.

He estimated that in the sixties, the area was turned into a “sanitary landfill,” which meant that it was covered over with dirt every day. This landfill took all sorts of trash. “It could have been recyclables; it could have been metal; it could have been anything, practically. Some of it very easily could have been petroleum products because they were not recycling petroleum, oil, and gas as they do today. Nobody thought anything of it,” said Mr. Beaumont.

At that time, some people would also burn trash in their backyards and deposit the ashes in the landfill. However, the practice was soon banned, and, as Mr. Beaumont noted, “That was when the landfills started filling up at a much more rapid rate, and town officials really had to come up with some way to mitigate the growth of trash in landfills.”

The Connecticut Resources Recovery Authority (CRRA), created in 1973, helped facilitate this process by serving as a semipublic entity to run waste disposal within the state. According to the Materials Innovation and Recycling Authority (the recently overhauled version of the CRRA) website, the organization’s first goal was to improve Connecticut’s waste disposal methods by “moving the State away from the process of landfilling.”

Connecticut took the goal of decreasing dependency on landfills seriously. According to the Connecticut Department of Energy and the Environment (DEEP), about 240 landfills closed in Connecticut between 1960 and 1995. In 1991, the state made recycling mandatory.

In the late eighties, when Wallingford was looking for non-landfill solutions, it developed a type of resource recovery system called a trash-to-energy plant. The plant, run by Covanta since 2010, burns trash from Wallingford, Cheshire, Hamden, North Haven, and Meriden in order to create energy. As The Record Journal reported in 2014, the ten-acre facility can burn about 420 tons of solid waste per day to generate approximately 11 megawatts of electric power.

However, this newfangled technology is not a perfect solution. Mr. Beaumont said, “I can tell you from being involved with the utilities commission: it’s not a very efficient means of producing electricity. Is it a way of getting rid of things? Yes, it is. Is it the best way?”

Not quite. With the push to reduce waste and recycle more, the trash-to-energy plant does not have enough trash to remain viable. Consequently, the contributing towns and CT DEEP are planning to convert the plant into a trash transfer station in the next few years.

As Mr. Williams, Mr. Wall, and Mr. Beaumont suggested, past approaches to waste disposal reveal themselves as problematic only in reflection. Repeatedly, people followed the “right”, or perhaps easiest, method of the time to dispose unwanted materials — whether that was discarding farm equipment, dumping urinals and ceiling tiles, or burning tires — but were unaware of the long term environmental and human impact.

Mr. Beaumont assured, “People were not about to go out and just wantonly destroy their property. Sometimes things would be done without thinking, without realizing what the impact was. People, especially farmers who were close to the land — the last thing they wanted to do was ruin their land. It was their livelihood.”

Connecticut is only beginning to look to a future of waste disposal that emphasizes the re-use of trash, a solution transcending dump-and-burn. Though the state has tried trash-to-energy plants, other options such as adamant composting and recycling have only come into mainstream thought recently.

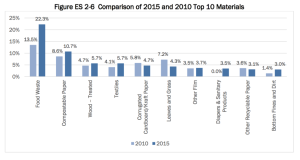

Composting remains an untapped resource. Currently, unlike recycling, separating organic material from the solid waste stream is not mandatory in Connecticut. According to the DEEP 2015 Statewide Waste Characterization Study, the most common material in the municipal solid waste stream in both the 2010 and 2015 Top 10 Most Prevalent Materials Studies was food waste and compostable paper.

Figure ES 2-6 shows the top 10 most prevalent materials in the MSW stream in both the 2010 and 2015 Studies.

Additionally, recycling rates have plateaued while population has grown, an issue with potential alarming consequences. According to the DEEP’s Solid Waste Management Plan, without improved waste reduction and recycling, Connecticut will have a greater need for disposal capacity at a time when “available land is in shorter supply, construction and operating costs are higher, and the public is less willing to accept additional waste disposal facilities.”

Reforms to recycling and composting will help Connecticut meet its need, according to the Public Act No. 14-94, to divert at least 60% of its solid waste by 2024.

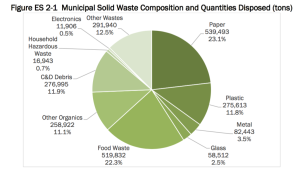

Figure ES 2-1 shows the composition and tonnage of disposed wastes in 2015, aggregating the Residential and ICI generator sectors.

But what does this really mean?

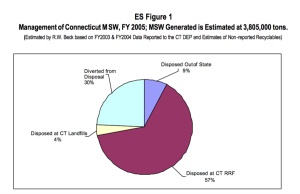

Connecticut has worked hard to decrease its landfill reliance; in addition to the approximately 240 already-closed landfills, CT DEEP lists only 26 landfills on the 2015 DEEP Active Landfill Sites in Connecticut chart. (Three of those are “No Longer Accepting Waste,” one is “Inactive,” and five have “Limited Capacity.”) However, according to the CT DEP’s Solid Waste Management, out-of-state disposal of Connecticut municipal solid waste increased from approximately 27,000 tons per year in 1994 to 327,000 tons per year in 2004. Although dependence on local landfills has decreased, it is at the cost of outsourcing waste to other states that are willing to pay for Connecticut’s refuse.

Nevertheless, human approaches to trash disposal will continue to develop. The Wallingford town landfill is now the site of a resident dump and recycling station. Past the chain link fence surrounding it, the cylindrical ventilation fans in the ground spin like pinwheels on a lawn. Small sycamores have begun to grow on the inclines of two or three flat-topped hills covered in thick, green grass, and in the distance fertile farmland lies in even rows under the rusted towers of high voltage power lines crisscrossing the sky.

The land is unexpectedly beautiful, almost a place for a summer picnic. It is hard to know what could be buried underneath. And, who knows: In the future, old landfills may be used for new purposes, such as the solar fields in Hartford, CT. Communities can develop a system of fair and sustainable waste disposal. Until then, the land and the trash and the people all have histories to tell.